This article provides an overview of actuarial and financial subjects related to Investment and Financial Market. Following the syllabus of IFM exam given by the SOA, it can serve as materials for students to prepare the exam, or for actuaries & other financial professions to consult for their work.

- 1. Mean-Variance Portfolio Theory

- 2. Asset Pricing Models

- 3. Market Efficiency and Behavioral Finance

- 4. Investment Risk and Project Analysis

- 5. Capital Structure

- 6. Introductory Derivatives - Forwards and Futures

- 7. General Properties of Options

- 8. Binomial Pricing Models

- 9. Black-Scholes Option Pricing Model

- 10. Option Greeks and Risk Management

1. Mean-Variance Portfolio Theory

1.a. Risk and Return of a Single Asset

Consider a single asset with return R (a random variable following a discrete distribution : \( \forall i = 1,…,n: P(R=R_i) = p_i \)). We are interested in calculating the mean and variance of its return (the variance of return is considered as the measure of risk in this framework): \[ E[R] = \sum_{i=1}^{n}{p_iR_i} \] \[ Var(R)= E[(R_i-E[R])^2] =\sum_{i=1}^{n}{p_i(R_i-E[R])^2} = E[R^2]-(E[R])^2 \] The standard deviation of R is : \( SD(R)=\sqrt{Var(R)} \)

Now the question is, how do we define the (rate of) return R for an asset? Let’s consider an asset (a stock for example) with price \( P_t \) at time \( t \) and \( P_{t+1} \) at time \( t+1 \). In addition, this asset pays a dividend \( D_{t+1} \) between \( t \) and \( t+1 \). Its realized return in the interval \( [t, t+1] \) is then the sum of capital gain and the dividend yield: \[ R_{t+1} = \frac{P_{t+1}-P_t}{P_t} + \frac{D_{t+1}}{P_t} = \frac{P_{t+1}+ D_{t+1}}{P_t} -1\]

In practice, the rate of return can be calculated on a daily, monthly, quarterly, semi-annual or annual basis, depending on the type of asset. one can easily convert the rate of return between these different time intervals (or basis). For example, an annual realized return can be deduced from the four quarterly returns: \[ 1 + R_{t+1} = (1+R_{Q1})…(1+R_{Q4}) \]

Please note that this is not the only way of calculating a stock’s return. In many cases, one is interested in calculating the log-return \( ln(\frac{P_{t+1}+ D_{t+1}}{P_t}) \) which turns out to be more convenient for developing mathematical concepts and formulas. You may also heard about the total return, which is calculated on an index with dividends reinvested in the stock. I’ll talk about the differences between the classic return and the log-return and about the total return in another post. You could also learn more about the rate of return from this article.

The return of an asset may vary from a given year to another, depending on its performance. One can be interested in the mean of all annual return, called average annual return, for a period of T years: \[ \overline{R} = \frac{1}{T} \sum_{t=1}^{T} R_t \] Once again, the “risk” can be measured by the variance: \[ Var(R) = \frac{1}{T-1} \sum_{t=1}^{T} (R_t- \overline{R})^2 \]

The standard error corresponds to the standard deviation divided by the number of observations: \[ SE(R) = \frac{SD(R)}{\sqrt{nb.obs}} \] with \( nb.obs = T \) in our example. The 95% confidence interval for the expected return is : \[ \left[ \overline{R} - 2 \frac{SD(R)}{\sqrt{nb.obs}} ; \overline{R} + 2 \frac{SD(R)}{\sqrt{nb.obs}} \right] \]

1.b. Risk and Return of a Portfolio

Once we know how to measure the risk and return of an asset, we can extend the calculation to a portfolio of assets/investments, by recognizing that the return of a portfolio is simply the weighted sum of return of each asset in it. \[ R_p = \sum_{i=1}^{n} x_iR_i \] with \(x_i = \frac{\large{\text{value of asset i}}}{\large{\text{total value of portfolio}}}, i = 1, …, n \) (Note that \( \sum_{i=1}^{n} x_i = 1 \)).

The mean (expectation) of the portfolio’s return is: \[ E[R_p] = \sum_{i=1}^{n} x_iE[R_i] \] The variance of the portfolio’s return is:

\[ Var(R_p) = \sigma_{p}^{2} = \sum_{i=1}^{n} x_i Cov(R_i, R_p) = \sum_{i=1}^{n} \sum_{j=1}^{n} x_i x_j Cov(R_i, R_j) \]

Note that one can also compute the latter term (the covariance of each investment/asset’s return) as follows : \[ Cov(R_i, R_j) = E[ ( R_i - E[R_i] )(R_j - E[R_j])] = \rho_{i,j} \sigma_i \sigma_j \] Again, given the returns of i and j over a period of T (years), we can estimate their covariance by: \[ \frac{1}{T-1} \sum_{t=1}^{T} (R_{i,t} - \overline{R_i}) (R_{j,t} - \overline{R_j}) \]

1.c. Diversification

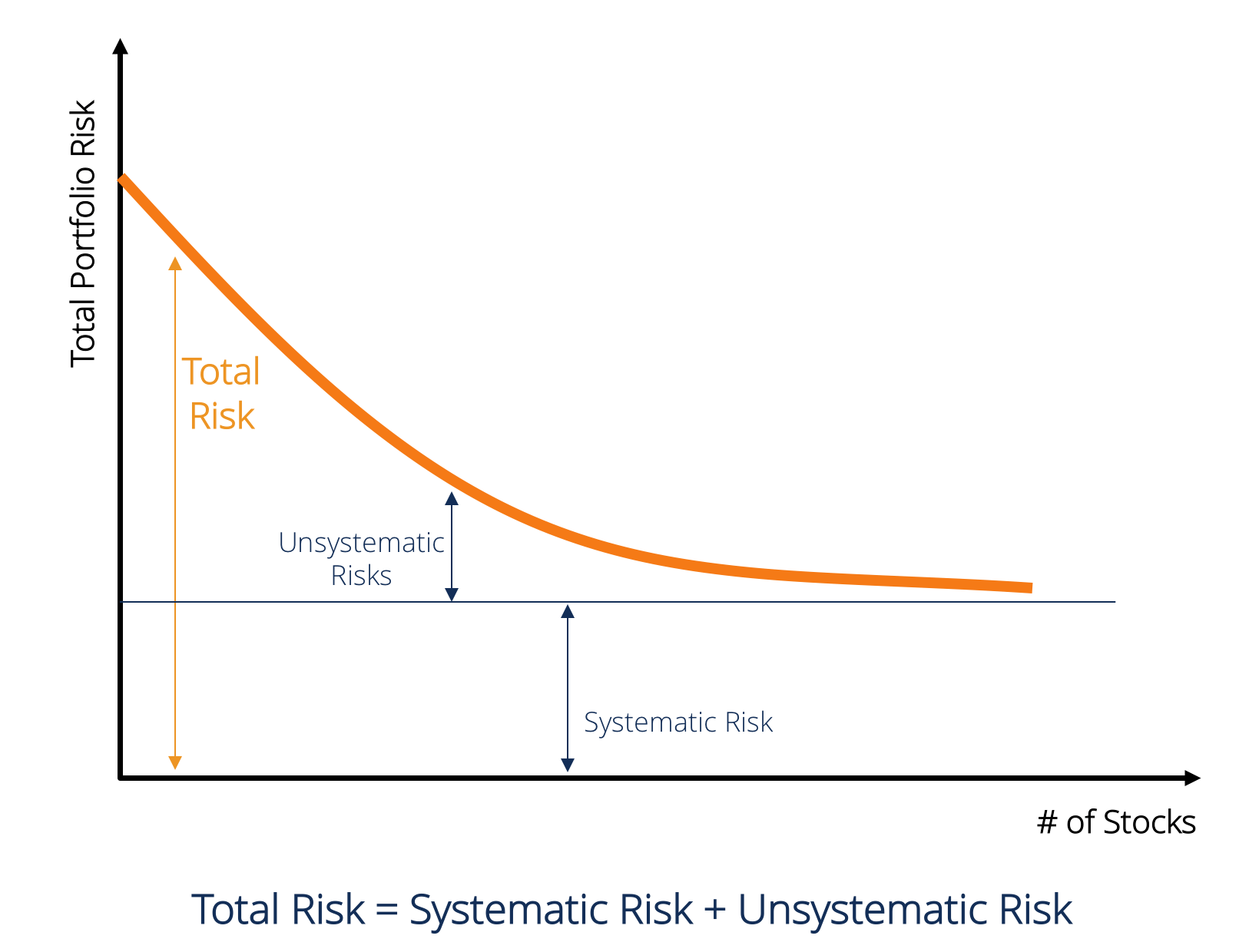

The total risk of a portfolio investment is decomposed by:

-

the systematic risk (a.k.a. market risk, or undiversifiable risk) which represents the fluctuation in the stock’s return due to market news,

-

the unsystematic risk (a.k.a. firm-specific risk, diversifiable risk, idiosyncratic risk) which captures the fluctuation of stock’s return due to firm-specific news.

Diversification helps reduce, or even eliminate the unsystematic risk in the portfolio. The risk premium for unsystemic risk is thus zero. The risk premium of a stock lies completely on its systemic risk.

(Source: https://corporatefinanceinstitute.com/resources/knowledge/finance/systematic-risk/)

For example, one can diversify its investment portfolio by investing in different stocks from different categories (tech, automobile, banking, service, etc.) in different countries, or combine stocks with bonds, real estate, etc. Combining different classes of assets allows investors to reduce the unsystematic risk but the systematic is unavoidable (as when the whole market is in chaos during the global financial crisis, when the economy is in recession, etc.)

The following formula shows how each stock’s volatility contribute to the portfolio’s volatility: \[ \sigma_{p}^{2} = \sum_{i=1}^{n} x_i \sigma_{i} \rho_{i,p} \] From the formula above, one can show that as long as the correlation is not perfectly 1, the portfolio’s volatility is less than the sum of each stock’s volatility.

By observing the diversification’s effect on a portfolio while increasing the number of stocks in it, we can see that the diversification’s effect is more significant initially but stagnates from some number of stocks. That’s where the total risk is reduced to its unavoidable limit, equal to the unsystemic risk. There’s no magic allowing to eliminate all risks in a portfolio investment. It’s because assets are somehow correlated with \( -1 < \rho_{i,j} < 1 \).

In a perfect world where we could find 2 assets i and j verifying \( \rho_{i,j} = -1 \) (hence their underlying risks could offset each other with an appropriate combination) we could construct a portfolio with zero risk. Indeed, \[ Var(R_p) = x_i^2 \sigma_i^2 + x_j^2 \sigma_j^2 + 2 x_i x_j \rho_{i,j} \sigma_i \sigma_j = x_i^2 \sigma_i^2 + x_j^2 \sigma_j^2 - 2 x_i x_j \sigma_i \sigma_j = ( x_i^2 \sigma_i^2 - x_j^2 \sigma_j^2 )^2 \]

By carrefully choosing \( x_i \) and \( x_j \), we could set the variance of the portfolio at 0.

Another hypothetical case where a portfolio could be risk-free is when we could find a countless number of stocks that are uncorrelated. Consider an equally-weighted portfolio of n stocks, with AvgVar the average variance of these n stocks and AvgCov the average covariance of the paris of stocks. We have: \[ Var(R_p) = \frac{1}{n} AvgVar + \frac{n-1}{n} AvgCov \] Since AvgCov = 0, the variance of the portfolio’s return tends to 0 when n tends to infinity.

To conclude this section, maybe a talk given by Ray Dalio, the founder and co-CIO of the world’s largest hedge fund, Bridgewater Associates, could get you more inspired by the advantages of diversification:

1.d. The mean-variance portfolio theory

This very simplified theory supposes all of the (unrealistic) following assumptions:

-

investors are risk-adverse

-

there’are no transaction costs nor taxes

-

the expected return, variance and covariances of all asssets are known and are the only criteria for investors to choose their optimal portfolio.

A portfolio is considered efficient if it offers the highest expected return for a given level of volatility. We can then draw the efficient frontier which connects all (volatility, corresponding highest expected return) points.